Interwoven: Jewellery Meets Textiles

The exhibition Interwoven explores jewellery that grows from the intersection between two disciplines – jewellery and textiles.

You see intersections in the craft materials and processes used in the work on display. The word describes ‘a point common to lines that connect’; for example, crossed or layered threads in textiles or wire in jewellery, used to make a surface or form. To intersect is also an intellectual or exploratory action. In the work of the jewellers featured it pinpoints how each has crossed the boundary between two artistic practices to find new and imaginative ways of working.

Every discipline has its borders; over time they shift through pioneering work that alters our understanding of the range of expressions that can be made. It is most often those who are comfortable exploring the margins of their subject that introduce the new and sometimes cause a revolution.

We see this in the seismic shift recognised as the New Jewellery Movement that started in the 1970s. This is the time when the earliest works in Interwoven were made by David Poston and Caroline Broadhead – Twist it Yourself (1974) and Neckpiece (1976). Each use textile materials and techniques – whipping brightly coloured cotton embroidery thread to make a choker and necklace – as part of the Movement that saw non-precious materials embraced, in combination with precious metals and on their own.

Broadhead recognises the potential to expand jewellery’s borders, as well as the skill underpinning this way of working: ‘I think jewellery is the most versatile and wide-ranging of the arts. It can encompass every material and can include so many techniques and ways of working – metalsmithing, carving, beadwork, casting, bio-design or computer-based processes, etc. Generally, for cross-disciplinary work to be successful, I think it is best to have a good grounding in one discipline to start with.’

From the perspective of a textile artist, Bauhaus-trained Anni Albers (1899-1994), writing in 1937, mirrors Broadhead in seeing the range of variables her chosen discipline offers: ‘Besides surface qualities, such as rough and smooth, dull and shiny, hard and soft, it also includes colour, and as the dominating element, texture, which is the result of the construction of weaves.’

Albers’ statement lists many of the characteristics of textiles that have attracted makers in Interwoven to explore their potential. She herself crossed disciplines, as a print maker, and in creating jewellery with designer Alexander Reed whilst both were teaching at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in the 1940s. Their work combined manufactured non-precious metal forms, such as washers, hairpins, paperclips and a metal strainer, with ribbon and cork, to create jewellery that now appears markedly ahead of its time and at home with the philosophy of making celebrated in Interwoven.

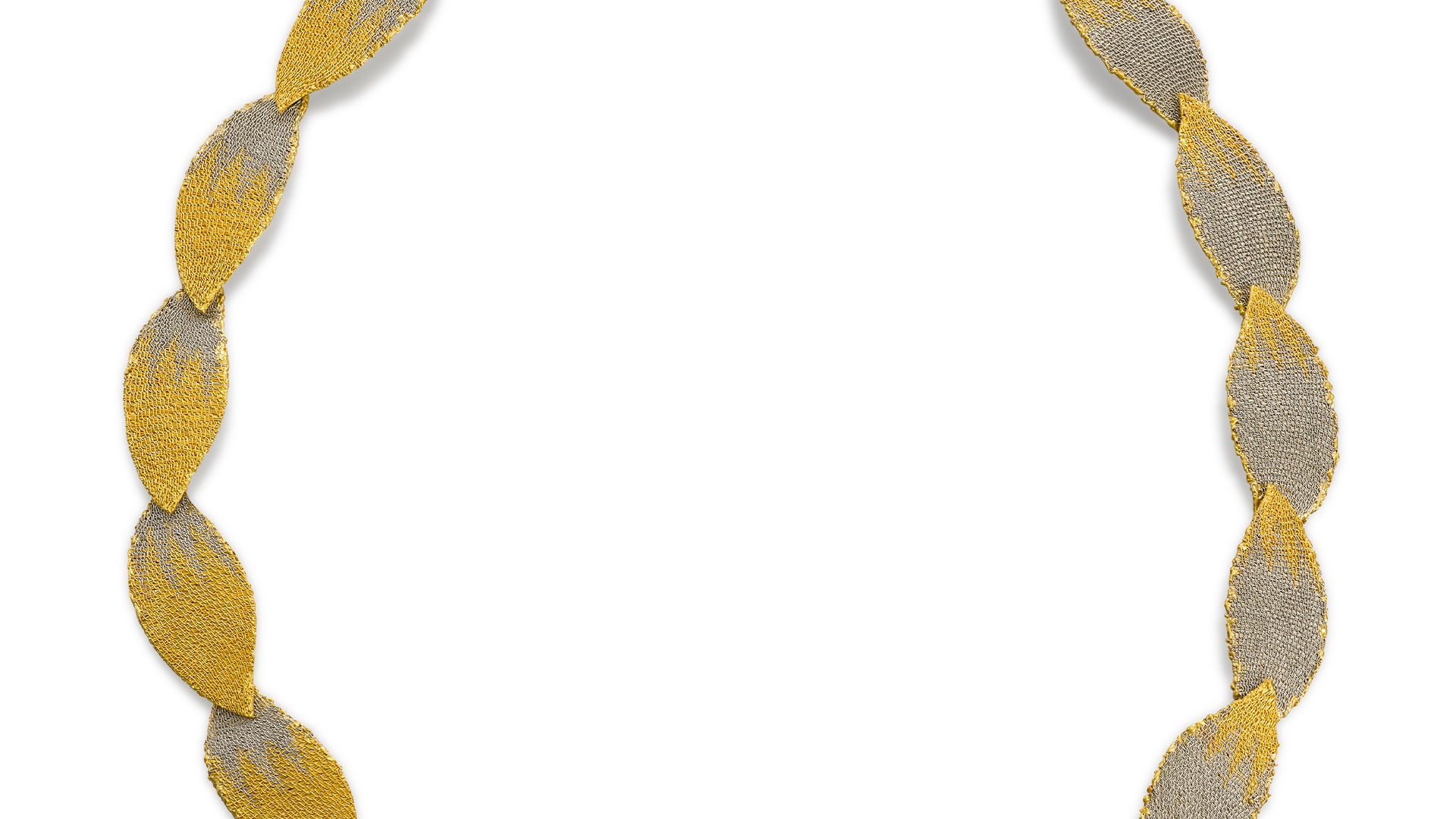

A boundary-pushing disposition is present in the attitude to making adopted by all those

featured in this exhibition. It is evidenced in Catherine Martin’s Necklace (2003), made with woven metallic wires in the style of traditional Japanese kumihimo braid. To perfect the transfer of this ancient technique in silk into a contemporary means of manipulating gold and platinum, she studied with textile masters in Japan, learning through collaboration.

Andrew Lamb, whose Optical Necklace (2001) and Lenticular Brooch (2012) utilise gold and silver wire to create surfaces and forms that describe the fluidity, texture and patterning of a soft textile, despite their fixed state, believes: ‘Collaboration is essential. It would be impossible to sustain a successful creative practice in isolation. I often find myself working into the early hours, absorbed in problem-solving or experimenting with materials and ideas. These moments frequently lead me to reach out to my wider network for input and advice.’

An ongoing collaboration with industry enables Gilly Langton to create the brightly coloured elastic she uses to knot and weave patterns around silver forms. In Spin Brooch

(2024) and Tug Neckpiece (2024) this material in electric blue creates tactile structures. Failing to find elastic in a chandlers or haberdashers that could hold vivid colours, Langton sought out a manufacturer who would make the material in pure nylon, in the weights required. The confidence to establish this relationship followed a residency at the University of Dundee, where she was able to use the facilities and expertise in the textile studios.

The jewellery in Interwoven is arranged into four thematic groups: jewellery made using textile materials, jewellery made using textile techniques, jewellery that is akin to a textile, and jewellery inspired by textiles. These groupings are not rigid; some pieces can be seen to fit into a combination or all these categories. They offer a framework for exploring the diverse ways textiles inform and expand the language of contemporary jewellery, drawing on the makers’ own words:

Anna Gordon: ‘The thing I like about wire and textiles is it’s about mark-making. I’m not actually weaving with wire, rather creating a surface. I’m interested in precision and making something well. I take the stitches – the object actions – and create a composition out of these actions.’

Caroline Broadhead: ‘I like things that are flexible and have a tactility. Textiles allow for colour and as the material we wear close to the skin, it has an important connection to us.’

Susan Cross: ‘Inspiration for my work comes from a deeply rooted interest in textiles, both in terms of borrowed techniques and a range of visual references. I grew up amongst women in my family who were very skilled at making, whether this was dressmaking, knitting, crochet or embroidery, and so it’s second nature to me to be continuing hand-making in this way.’

Caitlin Murphy: ‘For a while I didn’t understand how important textiles were to my practice. In the beginning I looked to paintings for inspiration. I began strip-weaving during the pandemic, first with paper. I love patterns, geometry and illusion. I realised that strip-weaving 0.1mm thin metal allowed me to explore scale within my work while also experimenting with pattern. As time has gone on, I have started actively researching textiles. Recently, I undertook an online course in ‘Weaving Techniques for Colourful Basketry’. It opened my eyes even further to the potential of textiles as a source of inspiration.’

Faye Hall: ‘Textiles are where my heart really lies, it has been a huge part of my life since I was little, and it never fails to inspire me to make. I like the unpredictability, the comfort and the possibilities that textiles offer and I love that I am now in a place where I can also create wearable items from this part of my practice. I find it fascinating how some of my textile approaches lend themselves to jewellery objects and how the lines of each discipline feel so blurred. I like being in the middle of the two.’

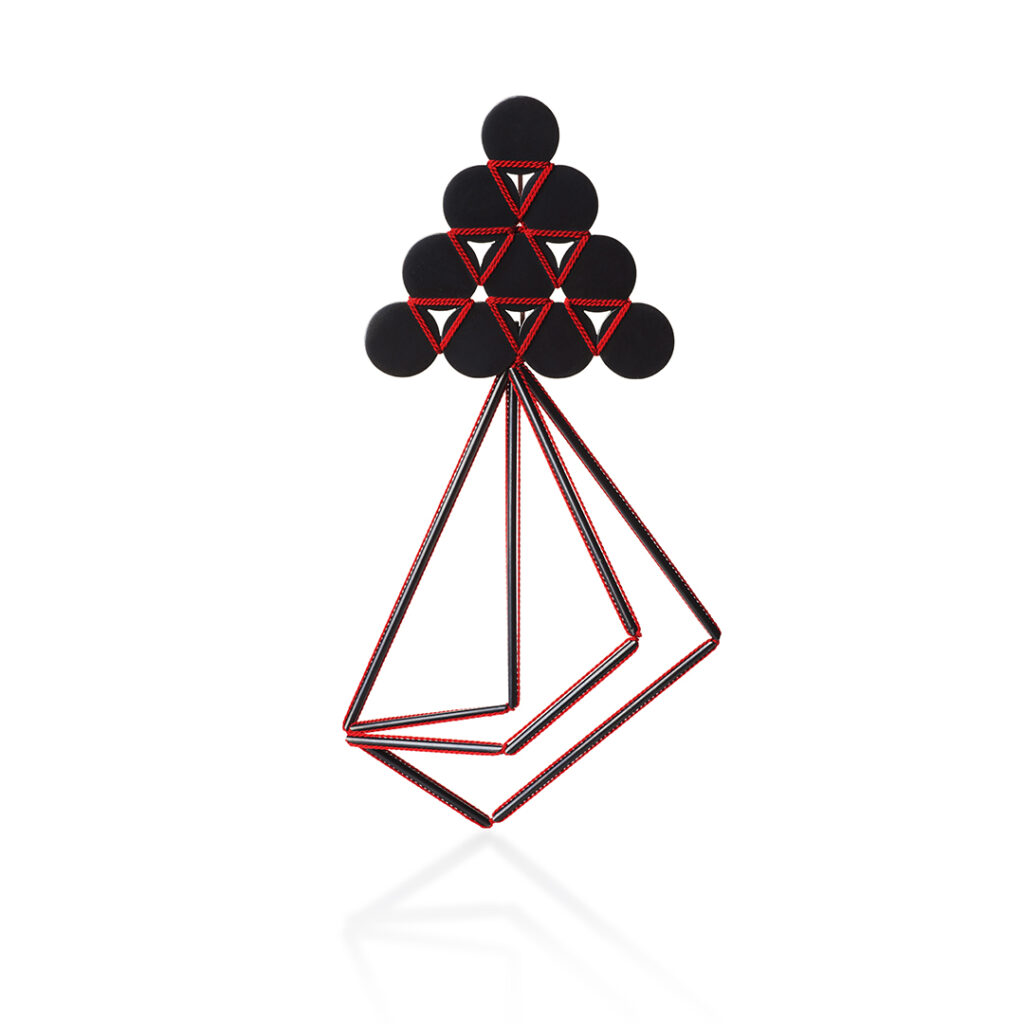

Working at the intersection of different disciplines is not unique to jewellers in Interwoven, it can also be recognised in the work of makers featured in Goldsmiths’ Fair’s other special exhibitions. In Watkins and Ramshaw, A New Vision, as the title alludes to, both David Watkins and Wendy Ramshaw have expanded our idea of what jewellery can be, embracing the lathe to create forms, as well as digital technologies, elevating non-precious materials and making jewellery that has new relationships to the body and display. Ella Fearon-Low’s installation Jewels for the Hall brings us sculptural-scale gems, and collaboration with a woodturner, as well as her exquisite use of Lucite to jewel-like forms, by carving, shaping and finishing it with the skill of a lapidarist working on a stone. Fearon- Low’s brooches Araish and Jaipur (2024) feature in Interwoven. Inspired by the textile paisley pattern, at the time of their making they were her largest brooches to-date, designed as a pair to be worn together or individually, the double-pin allowing a myriad of orientations.

Interwoven highlights one of the many points where different art and craft practices are informing each other and expanding disciplines. The results offer an extraordinary richness of creativity and design. The outcomes of the relationship between contemporary jewellery and textiles make a case for collaboration and finding more spaces where we can intersect.

Interwoven was curated by Charlotte Dew, Head of Public Programmes, Gregory Parsons, Associate Curator, The Goldsmiths’ Centre, supported by Programme Coordinator, Erin Sleeper.